It is a natural tendency for all of us to invest predominantly in companies active in our home country or the industry we work in. Unfortunately, this tendency can lead to portfolios that are not diversified enough. If you are predominantly invested in energy or mining stocks, you might on the one hand miss the returns achieved in technology stocks in recent years or suffer more than other investors if there is a major decline in commodity prices like the one we have seen at the beginning of this year in the wake of the Coronavirus outbreak in China.

Of course, one might compensate for this lack of diversification by knowing more about a company, industry or country than the average investor. Didn’t Andrew Carnegie say the way to become rich is to put all your eggs in one basket and then watch that basket? But the evidence is mounting that your performance becomes worse, the more you watch that basket.

Ask yourself, how often you have checked your investments or market performance during the Coronavirus outbreak?

Have you checked the markets and your investments more frequently than normal? If so that is understandable, but as I describe in my book “7 Mistakes Every Investor Makes (And How to Avoid Them)”, the very act of checking your portfolio makes it more likely to act impulsively and short- term oriented. If you look at a stock portfolio only once a year, you will experience a negative return on average once every four years. If you look at the same portfolio every day, you experience a loss on average every other day. Of course, most of the daily losses are small but every time you see a loss in your portfolio you are tempted to change something – especially in times of crisis like the outbreak of the Coronavirus.

Ask yourself, how often you have checked your investments or market performance during the Coronavirus outbreak?

What often happens in these situations is that investors can’t resist the urge to cut their losses and sell some of their holdings. Of course, they know that company X has a great business and will eventually recover, but for now, it is better to stay on the side lines and buy the stock back when risks have subsided.

What these investors inadvertently do is teach themselves to become traders in a stock they think they know really well. So they tend to buy and sell the same stock over and over again. Last time, they might have sold a little bit too late and experienced some of the losses from a recent peak, so they try to exit a little bit sooner next time, and even sooner after that. Every time familiarity with the stock increases and investors get the illusion that they know more and more about the stock because typically they buy and sell the stock not because the share prices moves but because of some fundamental event that influences the business.

And so the story continues until the next egg breaks...

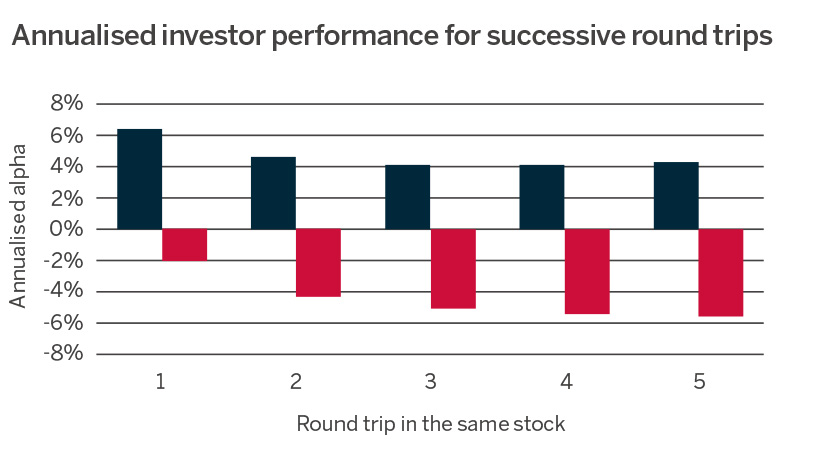

This behaviour is quite common. A recent study by Ellapulli Vasudevan from Aalto University in Finland looked at 308,000 Finnish and 76,000 US investors and found that two in five investors go on these round trips of selling a stock and then buying it again later at least once, while one in ten investors does that at least five times.

And every time the investor re-purchases the same stock again, the average holding period declines. On average a stock is held for about 6 months the first time, then four months the second time and three months the third time etc. And the performance gets worse and worse every time.

The chart shows the performance of the investments relative to the market for every round trip. Every time the investor buys the same stock again, the performance gets a little bit worse until one day, by accident, timing the market backfires and the performance is really bad. And at that point, investors often sell the stock, lock in their losses and leave this investment behind in disgust, vowing never to buy that stock again. They have watched their basket of eggs very closely until one of them broke, at which point they discard the broken egg and focus on the remaining ones. And so the story continues until the next egg breaks...

The lesson we learn from this is to hold a well-diversified portfolio and not to check it too often. In fact, if you have a portfolio that helps you achieve your long-term personal goals, it is typically enough to check its performance once a year, but certainly no more frequently than once a quarter. If you check it more often than that, you risk becoming victim to the process outlined in this article. It may feel as if you are becoming more familiar with the stocks you own, when in fact, you are becoming just more of a trader and less of an investor. And that is typically detrimental to your performance.

Joachim Klement is a research analyst and former Chief Investment Officer with 20 years’ experience in financial markets. He spent most of his career working with wealthy individuals and family offices, advising them on investments and helping them manage their portfolios.

Joachim studied mathematics and physics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, Switzerland, and graduated with a master’s degree in mathematics. During his time at ETH, Joachim experienced the technology bubble of the late 1990s first hand. Through this work, he became interested in finance and investments and studied business administration at the Universities of Zurich and Hagen, Germany, graduating with a master’s degree in economics and nance and switching into the financial services industry in time for the run-up to the financial crisis.

Illustration by Adam Mallett