When I started working in the Exhibitions Department at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) back in 2001, there was a reference document somewhat poetically called the mapa mundi.

In reality, this was little more than the temporary exhibition schedule laid out year by year with exhibition titles falling the demarcated time slots. Those titles in bold were confirmed, while those in Italics were yet to be ratified by the Exhibitions Committee. At the very end of the document was a long ambitious list of ideas that had been proposed but never acted on, which one day might move from the back page to occupy any one of the vacant time slots on the mapa mundi. Among all the ideas on that list, for many years, was arts of the Pacific, a vague reference to an idea that no-one had taken ownership of or driven forward. One of the reasons why it was there was because there had never been a major survey exhibition in the United Kingdom of this vast region coupled with the fact that there was no place in London to see Pacific material, as the British Museum had no dedicated gallery to show off its rich holdings. Move forward to 2012 when Kathleen Soriano, then Director of Exhibitions at the RA, came into the office and told me that she thought that she had found the right person to move this particular idea forward.

Over lunch at a Cambridge college the previous day, Kathleen had somewhat serendipitously sat next to Professor Nicholas Thomas, Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The subject of an exhibition on the arts and culture of the Pacific was discussed. Professor Thomas was not only very enthusiastic about the idea but had a rich collection of Pacific objects to potentially contribute to such a project. It turned out that Professor Thomas had an enviable reputation for his engagement with Pacific peoples and close connections to institutional colleagues around the world. Given that we had no in-house expertise to help drive such a project, Professor Thomas seemed like the perfect person to help us realize an exhibition on Pacific art. Director Soriano invited Professor Thomas to the RA to discuss the idea further with me as the best placed internal curator given my experience of working on exhibitions of non-Western art.

In order to move the exhibition planning forward, the project was presented to the Exhibitions Committee. The RA has a very active membership; Academicians hold the principal offices of President, Keeper of the RA Schools, and Treasurer, as well as chair various committees. Working alongside professional employees, the Academicians serve to ensure that the ratified decisions of the various committees are delivered. Oceania, as the exhibition was called, went before the committee and was duly endorsed. This meant that the project could proceed which gave us five years to conceive and deliver Oceania, as it was decided that the exhibition would take place in 2018 to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the RA and the first voyage of Lieutenant (later Captain) James Cook on HMS Endeavour in 1768. There was a further connection to the RA beyond sharing a date. Both the artists on the second and third voyages, respectively, William Hodges and John Webber, would later be elected RAs. A decision was also taken early on to focus exclusively on art produced in the region—that is, to not have any European views or portraits of the places and people they encountered. This was to be an exhibition based only on the art made by Pacific Islanders from the historic through to the contemporary. To my way of thinking, for an organisation like the RA to host an exhibition on non-Western art in its landmark anniversary year sent a strong signal about how the institution viewed itself.

For the RA to host an exhibition on non-Western art in its anniversary year sent a strong signal about howthe institution viewed itself.

The Pacific Presences: Oceanic Art and European Museums conference held in 2014 really pushed the agenda forward, bringing into sharp focus how challenging many of the issues surrounding the Pacific are - not just in terms of fraught and contested colonial histories, but also in terms of continuing issues of land and mineral rights and global warming. It was obvious that this exhibition would or rather could not be the conventional historical survey that the RA was used to putting on.

I was astonished by the depth and breadth of collections in Europe and the long history of collecting that emerged from those museum galleries and stores. The history of collecting (the provenance of the individual works) became a subtheme to the exhibition, highlighting the different histories attached to them. The principal difficulty was distilling the number of objects into a manageable number. We created long lists of potential loans to look at together. These were placed into distinct sections under the overarching exhibition themes of Voyaging, Settlement, and Encounter. At this point, given that so many objects are made of organic materials, the challenge was both budgetary and logistical: we had to determine how to conserve, transport, and safely install these works. Difficult decisions were made along the way. Some works were too fragile or simply too large to move. Others required long negotiations, especially once we knew that the most visited ethnographic museum in the world, the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris, had committed to hosting the exhibition after London.

These objects, despite having been removed from the Pacific and kept in museums in Europe, had retained their mana... and were still very much alive.

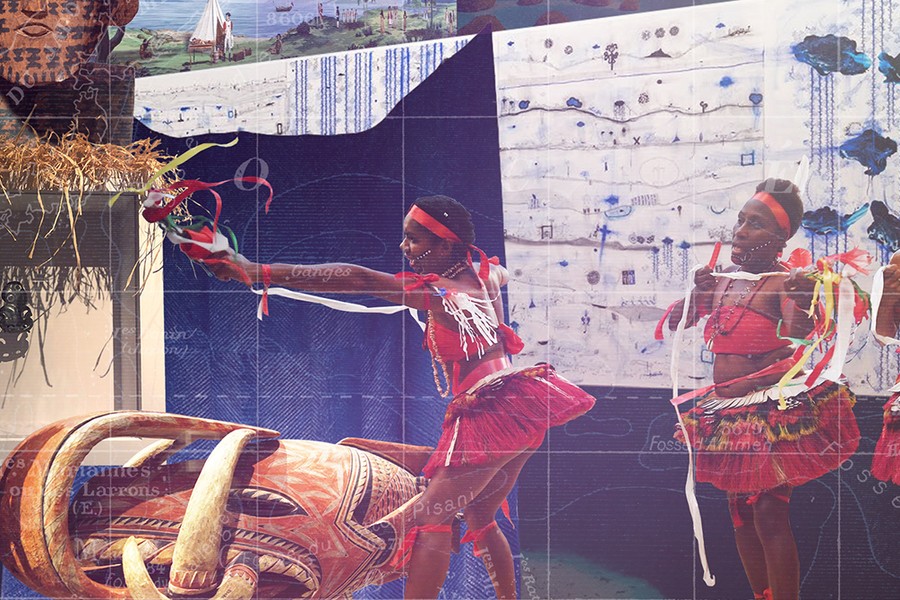

The inclusion of contemporary art was a major consideration. On a flying visit to New Zealand in November 2017, Artistic Director Tim Marlow and I met members of the Mata Aho Collective. The decision to include the Mata Aho Collective was made very late in the process after Flora Fricker, Exhibitions Manager, and I made an overnight trip to see Documenta 14, where Kiko Moana (2017) was showing, in the Landesmuseum, Kassel. We were blown away by the work and wanted it to be the first thing anyone saw when they entered Oceania, since for us it summed up the whole exhibition. We were convinced that its monumentality and elegant simplicity would surprise visitors. The negotiation was complex as the work was in the process of being acquired by Te Papa who generously agreed to lend it to us before it had even been shown in their own building.

Oceania was a complex and difficult exhibition to attempt to present, especially in a country with its own colonial relationship to the region, but we knew that we had to respect the people of the Pacific and, as was becoming increasingly apparent, highlight what these objects meant to them. It was during my visit to New Zealand that it became evident that the RA might have to extend an invitation to a descendant of Tuai should they choose to attend the opening reception in London. Thanks to an earlier meeting with the Curator Maori at Auckland Museum Tamaki Paenga Hira, to discuss the sensitive loan of the Kaitaia carving, I was made aware that we would need the permission of the Te Rarawa tribe to borrow this extraordinary object. The loan was agreed after the layout of the exhibition was presented and the position of the work was deemed appropriate.

So began a steep (but exciting) learning curve for all of us at the RA. Unfamiliar words like taonga (treasure), mana (respect, authority, power), and tapu (sacred/restricted) emerged particularly during our long negotiations with the Ministry of Foreign A airs and Trade (MFAT), which would be our main sponsor. Our responsibilities began to dawn on us, but it was not really until we started to receive these objects at the RA that the real power of these objects became apparent. Not used to dealing with such material, we discovered that these objects, despite having been removed from the Pacific and kept in museums in Europe, had retained their mana, their connection back to the communities and places of origin, and were imbued with ancestral power and were still very much alive. Temporal and geographic distance was no barrier to overcome these unbreakable connections. We had to accommodate things that we had never before come across: the prospect of offerings, that visitors may spontaneously sing or address objects, and that fresh water was required to cleanse themselves from any residual tapu. The private ritual dressing of Kuu from Hawaii, for example, with a malo (loincloth) made and donated by Auntie Verna Takashima and organized by Noelle Kahanu, was definitely not something the RA was used to exhibiting.

On the eve of the blessing ceremony in London a beluga whale was spotted in the Thames Estuary, an unheard-of occurrence.

The challenges came thick and fast, but the staff at the RA responded, embracing the exhibition like no other I have seen in my years working there. The excitement and sense of responsibility required in the temporary custodianship of these objects brought forth an outpouring of emotion and a hitherto unseen commitment. It was, and remains, the most emotionally charged and rewarding exhibition I have ever had the honour to be associated with. Never have I seen such direct and potent connections between people and objects. In that regard, Oceania was a revelation—and that was before the blessing ceremony.

On the eve of the blessing ceremony in London (which we had originally been advised would be a small, private event), a beluga whale was spotted in the Thames Estuary, an unheard-of occurrence. The news astounded everyone and was seen as very auspicious. The blessing ceremony was so large that it ended up closing Piccadilly, a major London thoroughfare, as the participants walked from Green Park to the RA to be greeted by Ngati Ranana (the London-based Maori cultural group) in the Annenberg Courtyard. The emotions ran high; the pain of separation, the agony of past histories, and the veneration of ancestors filled the galleries. It was electrifying. As the participants gathered around Kiko Moana, there was a sense that the exhibition had achieved something, even if was nothing other than to help them communicate with their ancestors and reconnect with their communities. It became evident that these objects needed to return home to be back in their place of origin among the descendants of those that had created them.

Illustration by Jordan Atkinson